fe can’t be easy as a Bank of England wonk dreaming up “stress tests” to check that Britain’s lenders are bomb-proof. They first had a go in 2014 and have devised new scenarios every year since, with a shrinking pool of options.

The inaugural test featured a UK recession in which GDP contracted 3.5 per cent, sterling lost 30 per cent, inflation hit 6.5 per cent, unemployment reached 12 per cent and house prices fell 35 per cent. It broke Co-op Bank, and Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds Banking Group were told to muscle up.

The following year the Bank tested the resilience of global balance sheets. Chinese growth stalled, the slump spread, deflation gripped the eurozone and the UK slid into recession. No bank failed but RBS and Standard Chartered came too close for comfort.

By 2016 the Bank was running out of ideas. Last year’s tests were a hybrid of the previous two, only harsher, and Barclays joined RBS and Standard Chartered on the naughty step. As for this year? It’s getting predictable. Another severe recession plus a secular stagnation scenario to stop the boffins getting bored: seven years of depressed growth and zero interest rates.

Monotony is dangerous. The more predictable the tests get, the easier they are to game and the less purpose they serve. Besides, recession is not the only risk. The whole point of financial reforms since 2008 has been to ensure that banks remain operational to serve the economy, to lend, make payments and fill cash machines. What if a crisis short-cuts the recession and hits banks’ operations directly, though? What if hackers shut down the financial system?

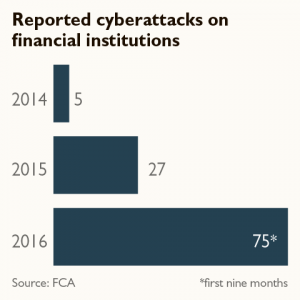

Seven years ago banks rated the threat from cyberattacks as zero. Today hackers are their second most challenging risk. More than 75 attacks were reported to the regulator in nine months last year. There were five in all of 2014.

Last year £2.5 million was stolen from 9,000 Tesco Bank customers. In January Lloyds’ online banking was shut down by a “distributed denial of service”, an algorithm that deliberately overloads the service. Most significant of all was the Bangladesh Bank fraud, in which $81 million was transferred to accounts in the Philippines in an attempted $1 billion cyber heist.

The Bangladesh hackers got into the pipes of global finance, the Swift payments system, and their success has emboldened others, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) says. Breaches undermine confidence in infrastructure and “highlight the growing risk from cyberattacks, whatever the motivation”, Sir Jon Cunliffe, the Bank’s deputy governor, has said. Modern bank robbers are benign compared with terrorists or Russian operatives.

In 2014 the Bank rolled out a cybertest based on threats identified by the intelligence community, which about 35 financial institutions have completed. After the Tesco Bank attack rivals began sharing information. The next step will be regular testing and spot checks based on evolving threats.

Regulators are right to focus on the danger. According to the NCSC, banks’ back-end systems are weak, leaving them vulnerable to an attack that could have “a major and substantive impact”. Financial regulation is underdeveloped, too. Andrew Tyrie, chairman of the Treasury select committee, fears that the set-up repeats past supervisory errors. The Treasury is nominally in charge of the cyber reponse but the Bank, the Financial Conduct Authority and the NCSC all have roles to play, blurring the lines of accountability.

For now, cybertesting is voluntary and there is zero disclosure. Banks are pretty bomb-proof against recession but there is some way to go with cyber. The last thing the Bank wants is a hacker heist.