Zimbabweans have endured shortages of fuel, food and water for decades: now the country is running out of cash.

Hundreds queue at cash machines in Harare, often in vain. When banks have cash to dispense, it can take two hours to reach the front of the queue but a daily withdrawal cap has been cut from $2,000 just a month ago to about $300. It is widely believed that the banks have had to curb withdrawals because President Mugabe’s government is illegally demanding loans that force them to raid customers’ savings.

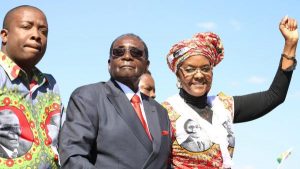

The 92-year-old leader, who often travels abroad and has been out of the country for the past three weeks, takes about $4 million in cash with him on every overseas trip, Tendai Biti, the former finance minister, said last week.

One bank customer, Barry Phillips, who runs a printing company, said that he queued for two hours only to be told that he could not withdraw the $6,000 he needed to pay his staff. “I asked the teller how much they were letting corporate customers have. A hundred dollars, he said. I’m panicking now. I can’t pay my workers, and they aren’t going to work without pay,” he added.

Zimbabweans fear that economic collapse is imminent. The economy nearly shut down in 2008, amid an inflation rate of 5,000,000,000 per cent. Mr Mugabe ordered banknotes worth about 1,000 billion Zimbabwean dollars to be printed. Quickly deemed worthless, the local currency was abandoned and black market US dollars took over. The US dollar became the official national currency in 2009.

Under Mr Mugabe’s rule, high taxes, labour laws that made sackings nearly impossible and demands that white-owned businesses hand over 51 per cent of their ownership to black Zimbabweans, have caused most of the country’s industrial base to shut down. The eviction of white farmers has, in effect, wiped out surplus farm produce. Fifteen years ago, supermarket shelves were filled with locally produced goods: now almost every product is imported — and that trade is seriously under threat.

“I’m struggling to pay my suppliers in South Africa,” said Vincent Hwende, who owns a supermarket. “Before, I could order a transfer from the bank and it would be in their account a day or two later. Now it’s taking three weeks, or longer. They won’t accept that. I just can’t operate any more.”

Eddie Cross, an economist, said that the country was running out of cash, partly because Mr Mugabe’s government was borrowing it illegally from the private banks, taking at least half of retail deposits. “Every bank in Zimbabwe is technically broke,” he said.

Rampant corruption accounts for a major chunk of state spending. Critics point to the home of Augustine Chihuri, the Zimbabwean police chief, on the eastern outskirts of Harare, marked by an enormous dome. Property consultants estimate that the building cost more than $5 million.

The International Monetary Fund has told the government that “profound economic transformation” is the only way to deal with the crisis. But Eldred Masunungure, a political analyst, said: “They don’t know how to take the country forward and there is little hope among citizens on how this regime can redeem us from the economic abyss.”

Mr Mugabe has been away from Harare for almost three weeks, travelling to South Africa, Singapore and Papua New Guinea with a delegation believed to be 60-strong, to attend a meeting of the Africa, Caribbean and Pacific group of states. He was the only head of state who turned up. Local media reported that he has travelled to Singapore for medical treatment ten times since January. He has also been to Uganda, Russia, India, Ethiopia and Equatorial Guinea, usually with a large entourage.

Obert Gutu, spokesman for the opposition MDC party, put his travel bill so far this year at $80 million.